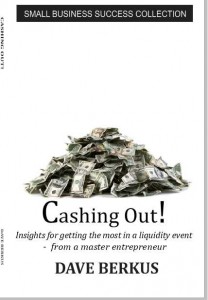

Dave’s note: We are privileged this week to host a post by Arthur Lipper, a well-respected member of the international financial community since 1954. He has served as advisor to and member of numerous financial exchanges, and was the founder and CEO of Arthur Lipper Corporation and co-founder and Chairman of New York & Foreign Securities Corporation. Today he serves as Chairman of British Far East Holdings Ltd. He has written numerous books and articles for entrepreneurs and investors, and was the publisher and editor-in-chief of Venture Magazine. Mr. Lipper addresses the issue of exits, and whether entrepreneurs should take the long view or cash out quickly when the opportunity arises.

By Arthur Lipper

It used to be that entrepreneurs started businesses as a life’s work, a mission. Many thought that they were starting companies for their children and grandchildren to inherit and manage. They sought to recruit associates offering a sharing of the vision resulting in lifetime employment as an incentive for maximum effort and effective collaboration.

They financed their companies, to the extent possible, in a manner minimizing the cost of capital, planning for organic growth in the number of customers served and in associated  revenues. As the business owners had a longer-term perspective, decisions were made with greater deliberation and with a more conservative recognition of risk. The businesses frequently were the owner-manager’s only major asset.

revenues. As the business owners had a longer-term perspective, decisions were made with greater deliberation and with a more conservative recognition of risk. The businesses frequently were the owner-manager’s only major asset.

The role model for many business founders were successful companies such as Microsoft, Cisco, Federal Express, all large companies, conservatively managed and often started and still managed by an individual entrepreneurs, even if later they became public companies.

[Email readers, continue here…] Now, when first meeting with an entrepreneur, I ask simply, “Is the business being formed as a Keeper or a Flipper?” Being one or the other is neither good nor bad, but the needs and investment considerations are very different. Keepers are financed differently than Flippers, which are started with a plan to be acquired in a few years, once the value of the technology or business model is demonstrable.

In the case of technology and Internet-related companies, competitive advantage will have only a relatively short lifespan and that therefore the window of opportunity is not infinite.

Flippers financed by venture capitalists are more likely to hire executives having high level profiles and previous exit experience. The Flipper’s executives usually have significant equity holdings, either actually owned or reflected in stock options. Therefore, all of the decision makers understand that rapid growth of revenues or customers at the expense of profit is the primary objective in positioning for a good exit early in the game.

In today’s world, especially where the Internet or technology is involved, prospective publicly-traded company acquirers sell at significant price/earnings ratios and have large amounts of capital available. They are also very competitive, and highly value the intellectual property of the Flipper. Their “make or buy” decision is heavily impacted by the time required to make and the value of the Flipper’s brand. Creating brand is or should be a major focus for companies in industries where positive and immediate customer prospect recognition results in sales.

Betting on the traditional public stock market speculator’s “greater fool theory” has been just plain wonderful for the owners of the Flippers, as aggressive acquirer’s value determinations are based on future events, rather than achieved profitability and present balance sheet values.

Keepers are more likely to be in industries with slower growth rates and lower price/earnings ratios. In other words, those intending to own and manage businesses for longer periods are more conservative and risk adverse. They also tend to have invested more of their own money in their businesses.

What does all of this say about market levels and public attitudes? I believe we are witnessing a shortened attention span by most technology and Internet company managers and controlling shareholders, who tend to be younger, as do those financing and trading in the shares of early stage companies.

When, or perhaps if, there is a downward adjustment in public company valuations, many of the younger players are going to learn some of the lessons the older game players learned in previous downturns – that valuations can revert to the mean or lower as companies mature, or as economies suffer challenges. However, in the meantime the highly publicized transactions of very young companies being acquired for enormous amounts of money will be sirens prompting entrepreneurs to be Flippers, which is fine if they have a chair when the music stops, and if they can find their acquirer before heavy dilution from financing rounds takes its toll on equity value for those early investors.

funding will be limited, but that one hundred percent of less is perhaps more attractive than fifty percent of more, given the restrictions usually placed upon management of companies using outside investment funds.

funding will be limited, but that one hundred percent of less is perhaps more attractive than fifty percent of more, given the restrictions usually placed upon management of companies using outside investment funds.